Ramblings

For random or less serious writings

For random or less serious writings

A quick aside: for a long time, I was blind to the fact that Pope's villa, depicted in this painting by Turner, had not burned down or fallen over or met some other ridiculous fate, but was infact demolished in 1808! While I don't know the exact details surrounding its destruction - and won't find out to hold back tears - this is a real kick in the teeth for me...I remember how I felt when I discovered that I couldn't visit it (the grotto alone isn't a good enough excuse to visit Twickenham), but in a way this is worse.

School libraries are odd places, in that, almost in spite of their locations, they hold a great wealth of old knowledge (often, anyway, since there are some schools which were not founded too long ago - and I should say that the fact that many do not hold much at all is a disgrace!). We often expect to find old books in university libraries, or archives, or jumble sales, but I think there is something quite special about turning to a title page and seeing that what you're holding had been withdrawn by another student however many years ago. At my own, between the shelves of criticism and drama can be found a collection of English poetry, unsurprisingly beginning with Chaucer, moving past the Oxford Books ofs, and at some point at ankle-level collapsing onto Ted Hughes. By my stomach is Pope, organised in whatever way that critical essays come first, before Mack's biography, The Rape of the Lock, and John Butt et al.'s edition of the collected poems. It's an interesting affair, this one-volume - in it are not just the works but all the 'minor verse'; some of what is 'major', i.e., lumped in with The Dunciad, An Essay on Criticism, etc. is forgettable too: turn to page twelve, and you're faced with the tonguetwister of Waller: On a Fan of the Author's design, in which was painted the story of Cephalus and Procris with the Motto, Aura Veni[1] - this being included cannot be an indictment of John Butt and his editors (the goal is to collect everything, after all), but its being my first encounter with Pope was certainly consequential, by which, I of course mean, I snapped it shut five pages in and consigned its author to the mental compost heap of bad poetry. I was a reader, you must understand, who had no experience of poetry beyond Shakespeare, Housman, and the GCSE English literature potpourri.

Six months later, I found myself sitting by the same bookshelf in that library, waiting to be let next-door for my German mock exam. At the Stygian banks (well, it was okay) I grabbed for The Rape of the Lock...it was all very confusing. Whether I sought a lesser boredom or had forgotten my dogma, we can't know, but I actually - would you believe - quite enjoyed my time. The week (which was all mock exams) progressed under a film of Pope, and after a biology...event...by which I felt quite empty, I checked out the same John Butt edition. In bed, I skipped the silly imitations and translations, and pushed on towards the four Pastorals of 1704. I had had a minor encounter (whose specifics I can't remember) with Winter in the preceding months, in which I admitted to myself that the lines

Behold the Groves that shine with silver Frost,

Their Beauty wither'd, and their Verdure lost.[2]

were quite pleasant (in retrospect, they're dwarfed by much else), but for whatever reason, I never read the rest of the poem - forget the other three. It was only now that I sat down and read them, start to finish, was completely absorbed, etc. (why do you think I'm writing this?). Most importantly, they shook a misconception I had of Pope, which was his 'classicism'. I use this word in both its directions - which you can probably anticipate - but I shall begin with its 'classicist' quality, that is, its - supposed - reliance on the reader having some understanding of Greco-Roman literature and mythology.

The very pastoral form is an ancient one, as are most; Pope himself identifies it as a line starting with Theocritus and then Virgil („'Tis therefore from the practice of Theocritus and Virgil, (the only undisputed authors of Pastoral) that the Criticks have drawn the foregoeing notions concerning it.“),[3] and writes that any merit of his own „is to be attributed to some good old Authors, whose works I had leisure to study“. But there is a stronger connection, which is that Pope's poetry is full to the brim with references to Homer (whom he translated), Virgil, Ovid, etc., and unlike in Shakespeare, where these are no more than craftily figurative, Pope takes various literary and mythological characters and allusions as significant elements in much of his work. To my twenty-first century ear, however cleansed in a little learning linguae latinae (!), these sounded quite pompous - as if Pope were violating his own maxim that „Some by Old Words to Fame have made Pretence; / Ancients in Phrase, meer Moderns in their Sense! / Such labour'd Nothings, in so strange a Style, / Amaze th'unlearn'd, and make the Learned Smile.“[4] Yet, of course, this is not the case; among Shakespeare's audiences were both cobblers and tribunes, and while the former were uneducated, culture had been suitably permeated by the subject of these allusions that everybody understood the gist. Pope's readership were - obviously - not regular people, but this does not mean...Papists (is that the fandom name?)...were a mutual admiration society who prided their understanding these references - rather, this aspect of Pope's writing had the capacity to be more effective than in Shakespeare due to its guaranteed comprehension (it wasn't, of course, because Shakespeare was superior in nearly every sense). Either way, having come to the conclusion I did, I ranked what I knew of Pope with a few lesser Housman poems,[5] in their to-my-mind pointless reliance on mythology (Housman was a classicist, but as far as I know, his audience were not). The Pastorals, I think, deal with this allusions quite well, because they don't feel like asides. This isn't just in the sense of 'imersion' - namely because a text keeping readers at an arm's length is not necessarily a bad thing - but in that they work as placeholders in the narrators' and characters' speech (and, surely, that's the opposite of the charged 'literary exhibitionism').

The second meaning of 'classical' which I would like to discuss is the allegedly doctrinal aspect of styles not just in poetry but also music and visual art. S.M. Schreiber, if my memory serves me right, writes in his book An Introduction to Literary Criticism that the classical ethos can be compared to the Parthenon, in its symmetry and its remaining within a set of defined boundaries. I am giving you this information, but I won't comment on it; I couldn't say whether it's true or not, and in the same way I don't know enough to decide whether there is a direct relationship between the style and this supposed part of the ethos. But it is possibly good context for the other complaint I was wont to make about Pope's work, of his insistence on the Heroic Couplet, which I saw as direly monotonous and uncreative. In my view, the Heroic Couplet is much like the balanced phrase. There are two ways of looking at either: a rigid, repetitive formula by which composers could churn out same-ish music (some did), or simply a rhythmo-melodic device which was much less conscious than the ingenious Greek meters of Olivier Messiaen or elements of the post-war serial music. I certainly take the second position today; I think such a technique can be judged more so on its application than its very definition. But it is exactly here where a great similarity between Pope's Heroic Couplet and the Mozartean balanced phrase; they perfected it, but succeeded a wealth of lesser usage. In the former case, we could look to Nicholas Grimald. Ruth Wallerstein observes that 'in sixteen sets of his occasional verse and epigrams, giving a fair body of continuous couplets, 97 per cent of the couplets are end-stopped; the lines have masculine rhymes on strongly accented syllables'.[6] Perhaps it is possible to look at this in relation to a character such as Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf, who, when compared to Mozart, is quite inferior. In the first movement of his sixth string quartet, we see the following theme (outlined in red) –

– which is repeated until the listener wants to tear his/her hair out! Edward Lowinsky, who pointed this out, further describes Mozart's Ein musikalischer Spaß, wherein such poor command is made fun of, as 'unable to construct a phrase properly: the antecedent goes the same way as the consequent, the consequent is sequent, the antecedent no antecedent, the ending the same as the beginning.'[7] If we turn our eyes to Mozart's Sonata K.311 for piano, the second subject of the first movement is an excellent example of how Mozart develops a theme on a smaller scale: between the two repeats, the significant melodic difference is the second's ornamention and altered articulation. Even within a single repeat - say, the first - the accompaniment does not follow a strict pattern but instead moves in free counterpoint; while an editorial slur in the Bärenreiter urtext covers the whole of the third beam-group of accompaniment quavers, it seems Mozart had suggested two – from the B up to F#, and from D back to the same B. In these two cases, it is not so much the features' very being which differentiates this work of Mozart from von Dittersdorf's string quartet Kr.196; it is Mozart's capability of working creatively over a system which can often be reduced to 'conceptual blocks' – and eventually the repetition of ideas according to preconceived models, and trends of tonal movement – which sets him aside from his contemporaries, and shows that he 'mastered' the phrasal equilibrium which had come to favour in much the same way as our subject, Alexander Pope, developed the couplet.

Thematically, what I find particularly beautiful about these four poems is the nestling of human love within nature. We read in Spring. The First Pastoral, or Damon that 'Soon as the Flocks shook off the nightly Dews, / Two Swains, whom Love kept wakeful, and the Muse, / Pour'd o'er the whitening Vale their fleecy Care, / Fresh as the Morn, and the Season fair'[8] (etc.). I am using this particular section here not just to demonstate the setting in which these lovers loved, but also to point out that the characters' relationship is one which moves in time alongside the cycles of nature (this is of course illustrated by the way Pope has decided to arrange the set of four: the year's seasons) – which does not mean that the poems illuminate any great truth of the world. The point is supported by my personal enjoyment. This is not a critical essay. But, since a Vlogbrothers video published today by John Green (At Least There Are Trees), I have been thinking that it is quite amazing that nature is 'going on' so to speak, while we go about our own chores - hence, I might, briefly and finally, say that Pope's having written much more than simply of the landscape drew me in.

1. This is from a series of imitations of other poets.

2. Pastorals, in J. Butt et al., ed., The Poems of Alexander Pope (London, Methuen, 1963), 136.

3. Ibid., 121.

4. An Essay On Criticism, in Butt et al., ed., 154.

5. I can't remember their names and I don't have the book in which I read them to hand, but they're not in A Shropshire Lad. If you see them you'll know what I'm talking about, I think; the book was The Collected Poems of A.E. Housman (Jonathan Cape, 1987).

6. R. Wallerstein, 'The Development of the Rhetoric and Metre of the Heroic Couplet, Especially in 1625-1645', PMLA, 50/1 (1935), 167.

7. E.E. Lowinsky, 'On Mozart's Rhythm', The Musical Quarterly, 42/2 (April 1956), 170.

8. Pastorals, in Butt et al., ed., 124.

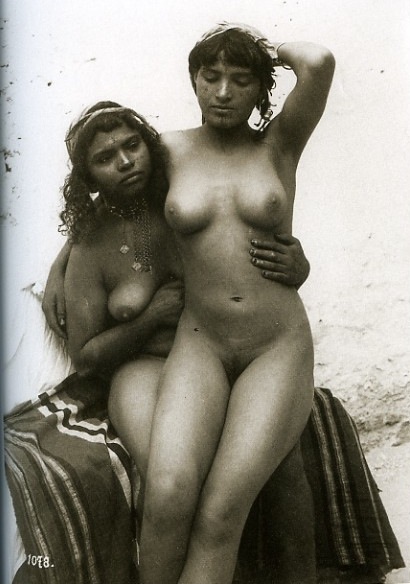

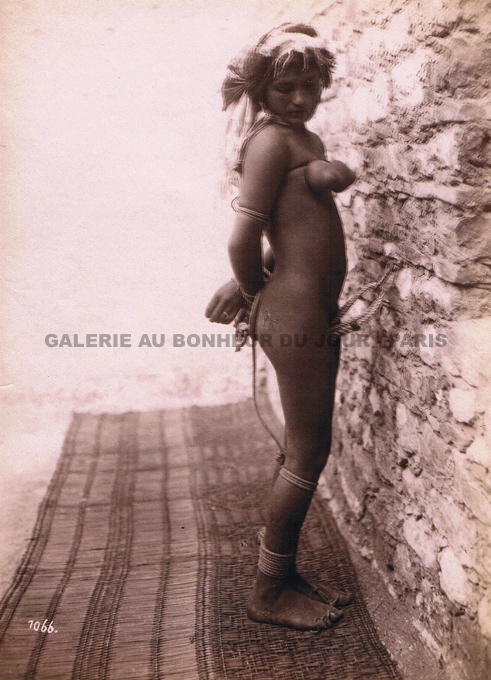

While photographers Lehnert and Landrock are best known for their orientalist photographs of north African 'life', possibly less known (though I'm no expert) are these two nudes of Tunisian women, taken in 1909 and 1904 respectively (see below).

On the left are depicted two girls, who cannot be through their teenage years. The image plays into the trope of young girls acting intimately with one another: the model on the right (hand in hair; lighter complexion) keeps an unnotable downward gaze and neutral expression, but the other, on whose lap she sits, looks upset. Though I know little of the specifics of this picture, I would struggle to believe that these poor girls sat and posed for a reason other than money. The second photograph, taken in 1904, shows something more explicitly disgusting: a Tunisian woman bound at her hands, calves, ankles and chest, with violence furthered by her having been turned to face the wall. To my mind this is a fantasised depiction of rape – specifically of indigenous people by the whites who captured and bought such images.

It may be that we witness here an alternative to the 'jewel of the east' – a more overtly racist depiction of the native woman. A contrast between the two is in the first image; the girl on the left is distressed, darker, ethnically decorated and to the white man an example of the ignorant, suffering Arab; on her lap is something much more sensuous, who is to be desired. Ultimately, the colonist desires that either be in ropes.

Prefatory note: I write poetry semi-regularly. My technique is normally to, once I've finished something, not look at it for a week or two then come back to it and pass judgement - which is normally a negative one. As I haven't put anything on my writings page in a while and this 'ramblings' section is completely bare I thought with the beginning of 2025 I could share two of my poems. As a bit of a warning, I better say that even the poems with which I'm happy do not hold up to any critical standards. I'm not so deluded to be an aspiring poet!

The charity case is

here antique.

Where do they park their cars

asks boyish whine,

of Dharavi Madonna

and little spluttering, yelling,

red-faced junctionthing

October sun-fried pigtail

shooed by air-conditioned fingertips

nicely rounded claws

who point and maim

Their veins’ icewater under escort

from walking sandpaper.

“I wonder who she is,

what she likes,

where she’s from”:

a little one’s contribution

How innocent –

say shoulders the seat before.

It seems to be a family

Of three or four, or five.

They barge into the sky

Racketing pre-planned circles,

Singing down to us

Or calling, rather – but what?

And they must be taunting

Surely – to mill around in naked thick

Bedraggled, yes, but perhaps offset

Then take off when we dare admire

What little is to be!